USS Constitution captures HMS Guerriere, August 19, 1812, one of the most significatnt American successes of the War of 1812, that helped give birth to the legend of "Old Ironsides" popularized by the 1830 poem of that name by Oliver Wendell Holmes, one of the iconic American national symbols to come out of the war.

My long-time colleague historian Dr. Martin K. Gordon is offering in March and April what I would suggest is a recommended overview of the War of 1812 in the Odyssey adult continuing education program at the Johns Hopkins University's Homewood campus. Dr. Gordon is the master of ceremonies for our annual National War of 1812 series held usually in Baltimore the first Saturday of October (watch for news of this year's upcoming event, due to be held on Saturday, October 6). Many of the speakers in the course have spoken in our symposium series and I plan to attend as a student--the campus is just across the street from me where I live off University Parkway in Baltimore. Hope to see you there!

Here are the details of the course:

The War of 1812: A Bicentennial for Baltimore and the Nation

Martin K. Gordon, PhD, Program Coordinator

The War of 1812 marked the culmination of sixty years of fighting for the North American landmass east of the Mississippi River—the region now composed of Canada and of the eastern half of the United States. When the fighting started in 1754, the American colonials, the British, the French, and the Native Americans all fought for control. Fifty-eight years later in 1812, the Americans, now independent, fought the British, the Canadians, and the Native Americans for ownership in Canada and on the Ohio and Southwest frontiers. But now there was a new challenge.

The 23-year-old United States had maritime interests to protect in addition to its landward thrusts. This was the era when Baltimore earned its reputation as a “nest of pirates” for its profitable privateering. Meanwhile, conflict on the Great Lakes and on land on both sides of the border with Canada strengthened both American and Canadian national identities.

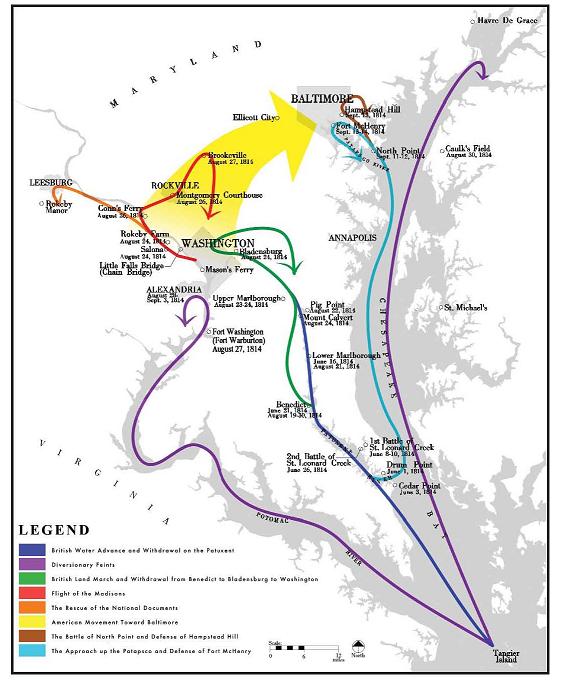

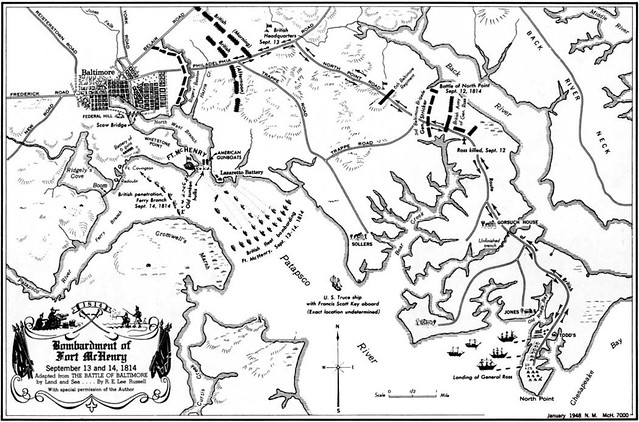

Along the East Coast, the war gave us “The Star Spangled Banner,” commemorating the heroic defense of Baltimore, after the British burning of Washington, as well as continued growth for Baltimore and its shipbuilding and trade businesses.

To the southwest, Native Americans forever lost their lands east of the Mississippi to Andrew Jackson’s forces. Jackson then went on to work with the real pirates of Barataria Bay, Louisiana to defeat the last British invasion at the Battle of New Orleans.

Through slide lectures and guest speakers, participants in this course learn of the victories, defeats, and historical legacy left all around them by this war, which played such a crucial role in confirming the independence and westward growth of our nation.

March 8. The Causes, Conduct, and Consequences of This War

With its causes rooted in the outcome of the American Revolution, the War of 1812 was fought along the land and maritime frontiers of the new nation. This comprehensive overview prepares participants for the sessions to come and for their own readings and touring after the course. Martin K. Gordon, PhD, Program Coordinator.

March 15. The Maritime War Along the East Coast

The Royal Navy had long practiced blockading the coast of France during the Napoleonic Wars. But in blockading the United States it didn’t have enough ships. While the United States Navy contested the blockade, winning its ship to ship fights with the British, Maryland merchants, especially from Havre de Grace and from Baltimore took advantage of every opportunity to damage British commerce and enrich themselves through privateering. William S. Dudley, PhD, Director Emeritus, United States Naval Historical Center and author, most recently of Maritime Maryland: A History.

March 29. Baltimore “a nest of pirates”

Baltimore started its participation in the war before it even started, with rioting so violent to give one example, the Revolutionary War hero and father of Robert E. Lee, Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee, never recovered from the beating he received during those protests. Baltimore’s resistance to and contributions to the war effort including its successful defense in 1814 are the subject of this talk. Scott S. Sheads, author, popular lecturer, speaker on PBS’s 1812 documentary, most recently co-author of The War of 1812 in the Chesapeake: A Reference Guide to Historic Sites in Maryland, Virginia, and the District of Columbia.

April 5. Fighting in the West

Future president William Henry Harrison made his reputation fighting Tecumseh and other Native Americans and their British allies for control not only of Ohio, but of the Old Northwest and even into Canada, winning the only major American victory during the several attempts to conquer that territory. Martin K. Gordon, PhD.

April 12. Fighting in the South: Andrew Jackson and the Creek Campaign

In 1814 during the Creek War, Jackson’s forces won a crushing victory at Horseshoe Bend on the Tallapoosa River. The Creeks, allies of the British, were no longer a threat on the frontier, and Jackson, also victorious at Mobile Bay and Pensacola was promoted to major-general. Harold W. Youmans, Esq., author, lecturer, editor emeritus of the Journal of the War of 1812.

April 19. Fighting to the North: Canada and the Great Lakes Campaigns

The United States Army and Navy along with the states’ militia made several attempts to conquer Canada. The Navy gained control of the Great Lakes, but the land forces were unable to follow up with comparable victories. Although they did capture and burn York, the capitol of Upper Canada, but at the cost of the life of Brig. Gen. Zebulon Pike, the soldier and explorer of the west. Richard V. Barbuto, PhD, Deputy Director, Department of Military History, Command & General Staff College, U.S. Army; and author of Niagara 1814: America Invades Canada, among other works.

April 26. Jean Lafitte, Andrew Jackson, and the Battle of New Orleans

In deciding to help the Americans at New Orleans in late 1814/early 1815, Lafitte and his gang went from the status of “banditti” to “gentlemen.” This presentation offers a look into the world of the Baratarians and, especially, their contributions to the American victory at the Battle of New Orleans. What role did they really play? How has the legacy of Jean Lafitte been transformed over the years? Tom Kanon, PhD, archivist at the Tennessee State Library and Archives in Nashville, has written numerous articles and essays on topics of the early American frontier period, particularly on the War of 1812 in the South.

Coordinator Martin K. Gordon, PhD, is a popular Odyssey series coordinator and speaker. Adjunct Professor of History, University of Maryland University College and adjunct member of the graduate faculties at the University of Oklahoma at Norman and at the American Military University.

Course no. 910.676.01 Homewood Campus

$180 (10.5 hours) 7 sessions

Thurs., Mar. 8–Apr. 26, 7:30–9 p.m. No class Mar. 22.

To download the Spring course catalogue as a pdf file, go to Odyssey Spring Course Catalogue.